Digital Evidence Expert

A mobile application built to help law enforcement collect digital evidence while protecting the privacy of all.

Context

In 2019, the Central Coast Cyber Forensics Lab (CCCFL) and California Cybersecurity Institute (CCI) worked with Amazon Web Services through Cal Polytechnic State University’s Digital Transformation Hub (Cal Poly DxHub) to improve the way digital evidence is collected at crime scenes.

Many crimes involve an electronic device that contains evidence that may be used in a court of law to exonerate or convict a person. To ensure we protect an individual’s privacy and that digital evidence is admissible in court, it needs to be collected accurately within ever-changing legal guidelines.

Problem

Per U.S. and State law, digital evidence is required to be collected in a way to protect citizens’ rights. If digital evidence is improperly obtained, it will be inadmissible in court. However, with new devices released weekly, persistent software updates, and constantly changing laws, investigators can struggle to know how to properly collect/store devices, and can even face trouble identifying what may be an important device to collect in the first place.

Solution

A mobile app that can act as a living library of electronic devices. The app will help law enforcement:

Identify devices that may contain digital evidence

Properly disable digital devices to prevent remote wipes, while protecting user privacy

Properly store and log collected devices

My Role

In partnership with Amazon Web Services, I led a team of two undergrads working on the project. I headed the UX portion of the application, and delegated tasks to the other team members. I also acted as the main liaison between the DXHub, CCI, and the CCCFL for collaboration on this project.

User Research

My team and I worked with stakeholders to bring in a group of 12 local law enforcement agents for design thinking workshops. Users were asked a series of questions such as how long evidence documentation should take, what the documentation process looked like, and what were the biggest roadblocks that they faced when collecting and documenting evidence.

In real-time, we then used construction paper and post-it notes to create rudimentary prototypes and ask for feedback with all stakeholders and potential users present.

Insights

After the brainstorming sessions, my team and I sat down and pulled out three major insights from our conversations.

Many potential users are not tech-savvy, so ease of use is of the highest priority.

There is a strong need to protect users’ privacy as well as suspects’ privacy. Without this, the app will go unused.

The efficiency and accuracy of instructions and logs are of the highest importance.

Prototype

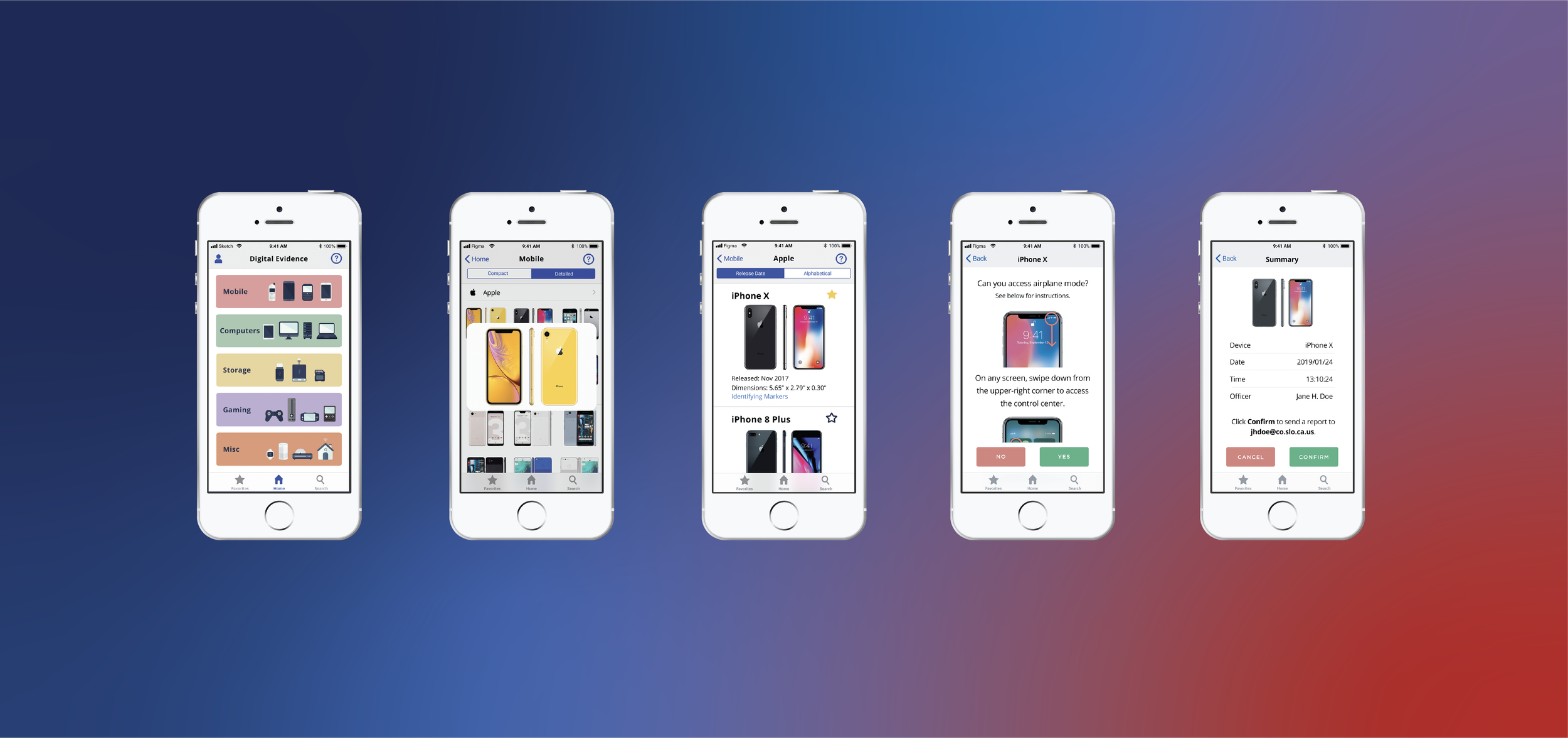

Using these insights, my team and I began working on multiple rounds of low and high fidelity prototypes using Balsamiq and Figma. We aimed to make the application easy to navigate by providing simple lists of instructions and allowing users to search for and find devices through categories.

First Round Prototype and Improvements

After conducting multiple feedback sessions and usability tests, alongside many others, 2 major improvements were made to the prototypes.

The first major improvement was made to the scope of the project itself. In original designs, I had planned for the app to keep location data when evidence was collected, the idea being that it would help officers later on when logging evidence. We also had tested the idea of actually using the officers phone camera to assist with the detection of device types, so that officers wouldn’t need to navigate through device categories at all

While law enforcement reps did agree that these features would be useful, they explained it would actually have negative impacts on the adoption of the app as a tool. They explained that if an officer used a phone to take a photo of a piece of evidence, their own device could be apprehended as evidence itself. Whether or not any photos of evidence was actually stored was irrelevant, because if a judge suspected that it was, their device could be apprehended.

In addition to this change, any and all location tracking was removed. Officers expressed that if there was even a suspicion that their location data was being used by their superiors to track them throughout the day, they simply wouldn’t use it. After these conversations, we proceeded with removing these features that I had previously assumed were no brainers from the project.

The second major improvement to the app was the scannability of it. Even more visual representations were added to the home page to help users quickly identify where different products were categorized, and more photos of devices were added to help users more quickly identify devices

Part of this improvement meant designing a new feature that would be used when an officer wasn’t sure about what device they were collecting. In this situation, they could view an “identifying features” page, where unique details about devices were shown.

Final High Fidelity Prototype

By the end of our project, the team and I were able to present to the stakeholders an app that was simple to use, easy to navigate, and included step-by-step instructions for users to move through. At the end of collection, a brief report would be created and sent to officers emails.

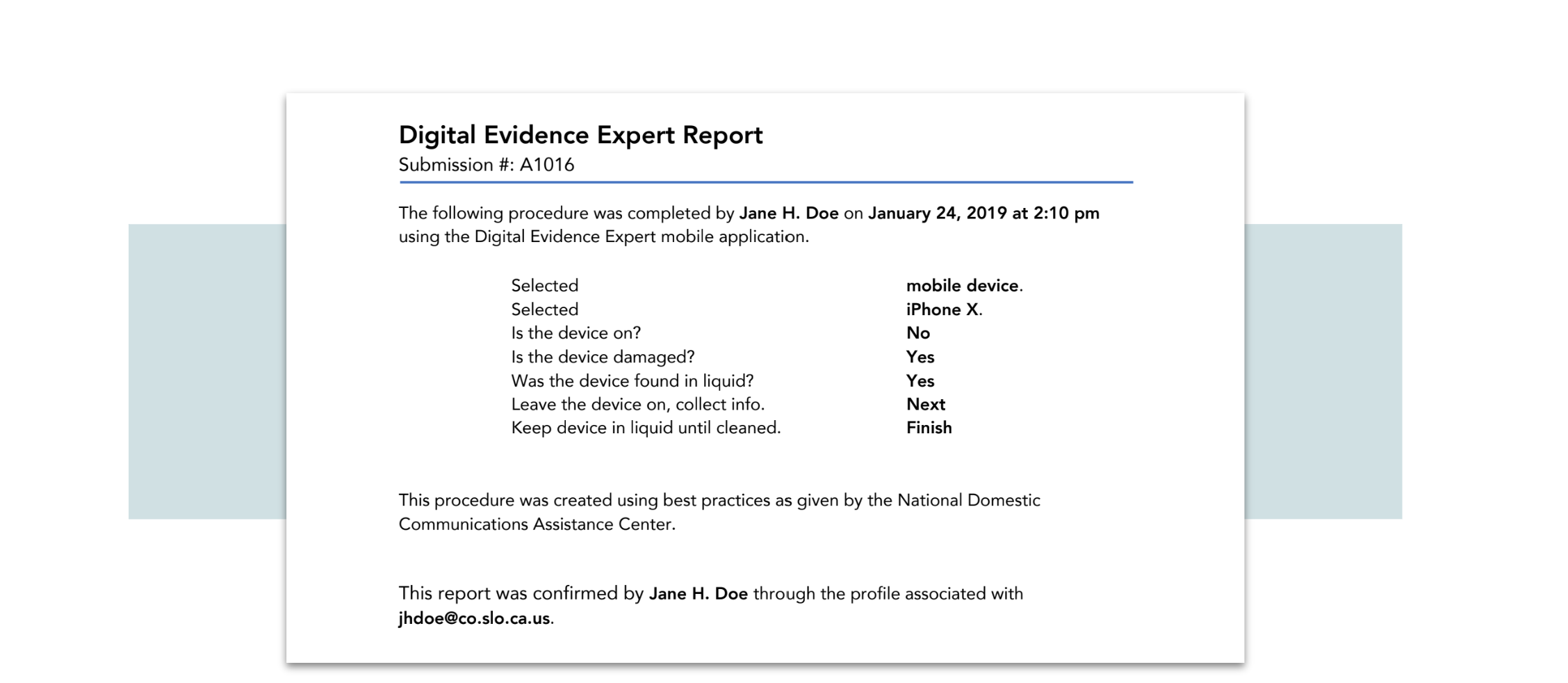

Peripherals

As part of the proof of concept, I created example reports that could be generated by the app for officers, giving not only them, but courts of law the confidence that devices were collected correctly and lawfully.

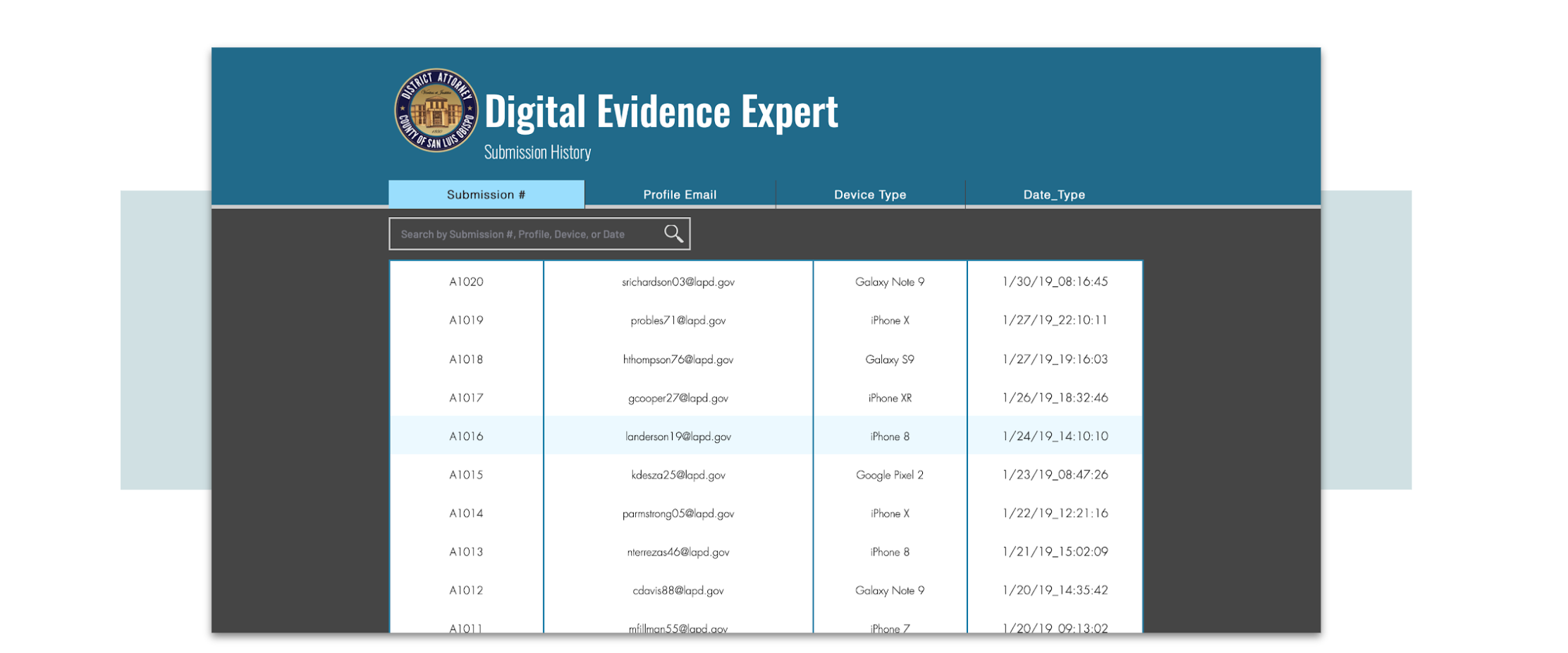

Additionally, I personally created a basic website, showing how officers and agencies as a whole could easily track collections, as well as gather metadata on crimes and digital evidence collected.

Results

After creating the final high fidelity prototypes, my team and I hosted a one last usability test and feedback presentation, where we ended up receiving plenty of qualitative and quantitative data that confirmed the success of the project.

During the final tests, the team and I had users collect two mobile devices of different types to ensure that at least some unfamiliarity with one of the operating systems would be present.

93.8% of users reported having NO trouble locating the types of devices they were collecting and expressed confidence that they had collected their devices successfully and lawfully

The average time needed to lawfully collect a device from start to finish was 63 seconds which stakeholders consistently expressed they were very impressed by and happy with. Anecdotally, some users approached me after the presentation unprompted to express excitement about the product, and explained how it would add value to law enforcement agents of all seniority levels.

Additionally the local district attorney's office as well as

Several statewide law enforcement agencies expressed interest in participating in a pilot program as soon as it was available.

It was fantastic receiving an overwhelmingly positive response from stakeholders, and I know that future iterations of the application would continue to improve the project as a whole. Currently CCI and CCCFL are working on getting funding to support the back end and functionality development or this proposed pilot project.